The Dagstuhl workshop on “Metric Sketching and Dynamic Algorithms for Geometric and Topological Graphs” I co-organized with Sujoy Bhore, Jie Gao, and Csaba Tóth concluded last week. This is the first Dagstuhl workshop I attended and also happens to be the first I co-organized.

My experience with Dagstuhl was nothing short of amazing. A typical day looks something like this:

- (morning) breakfast, attending a survey talk, group problem-solving for 1.5 hours, and lunch;

- (afternoon) group problem-solving for 1.5 hours, coffee and cake, another hour of group problem-solving, and finally, reporting progress, and dinner;

- (night) night walk or ghost hunting or playing pool, Cheese platter at 9:00 pm, and wine.

A short summary: food + drinks + solving problems. A week like this, away from the end of the semester, was much needed for me.

Dagstuhl provides food, coffee, and cakes. Participants pay for their travel costs (flights, trains, etc.), additional drinks (wine), and room (300 € for 5 days/ person). Organizers get free room.

1. Worshop Structure

As hinted above, we structured our workshop around problem-solving, peppered with invited talks and presentations (from junior participants). I have attended several other problem-solving workshops, and I really love this structure. On a typical day, we had one invited survey talk (about 1.5 hours) in the morning, and the rest of the day, we solved problems in groups.

Here is how it works. Before the workshop, we solicit open problems from participants. We used the coauthor platform to keep track of these problems. (Huge thanks to Erik Demaine for allowing us to use the platform.) On the 1st day of the workshop, problem proposers presented their problems, basically selling them to the workshop audience to attract people to work with the proposer on their problems. After all of these advertisements, we had 3 rounds of voting.

- First round: participants could vote on any problem that they are interested in working on, with no limit on the number of problems one can vote on. After this round, we crossed out problems that received less than 3 votes.

- Second round: Each participant can now vote for up to three problems with 3 different priorities: A, B, and C. Any problem getting less than 1 A vote was crossed out.

- Third round: Each participant can cast exactly 1 vote, and we form groups based on the votes.

Ideally, we want each group to have at least three people and not to be overcrowded (say six people or so). We ended up with six groups (out of 24 people), and every group had at least three people. Participants could also change their group during the week. We stole all the ideas above from various workshops we attended.

One thing that I appreciated from problem-solving workshops (instead of talk-based ones) is that I had an opportunity to work with new collaborators.

2. Invited Talks and Presentations

We invited four survey talks: (1) metric embedding by Arnold Filtser, geometric intersection graphs by Édouard Bonnet, (3) dynamic algorithms in geometry by Wolfgang Mulzer, and (4) routing on plane spanners by Jit Bose.

2.1. Metric Embedding

Arnold surveyed the recent developments of metric embedding into trees and other spin-offs. The talk covered:

- Basic ideas such as padded decomposition, Bartal’s embedding with distortion \(O(\log^2 n)\) and briefly touched upon the embedding with distortion \(O(\log n)\) by Fakcharoenphol, Rao, and Talwar.

- Online metric embeddin, where points arrive online and the decision to embed is irrevocable.

- Embedding into spanning trees: classical results and a recent embedding by Becker, Emek, Ghaffari, and Lenzen using low-diameter decomposition.

- Embedding planar/minor-free graphs into low-treewidth graphs.

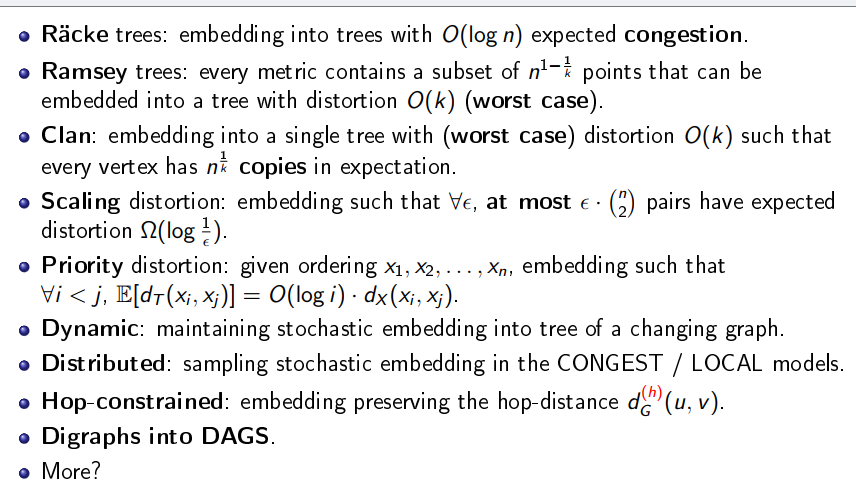

And a list of spin-offs that are not covered in detail.

2.2. Geometric Intersection Graphs

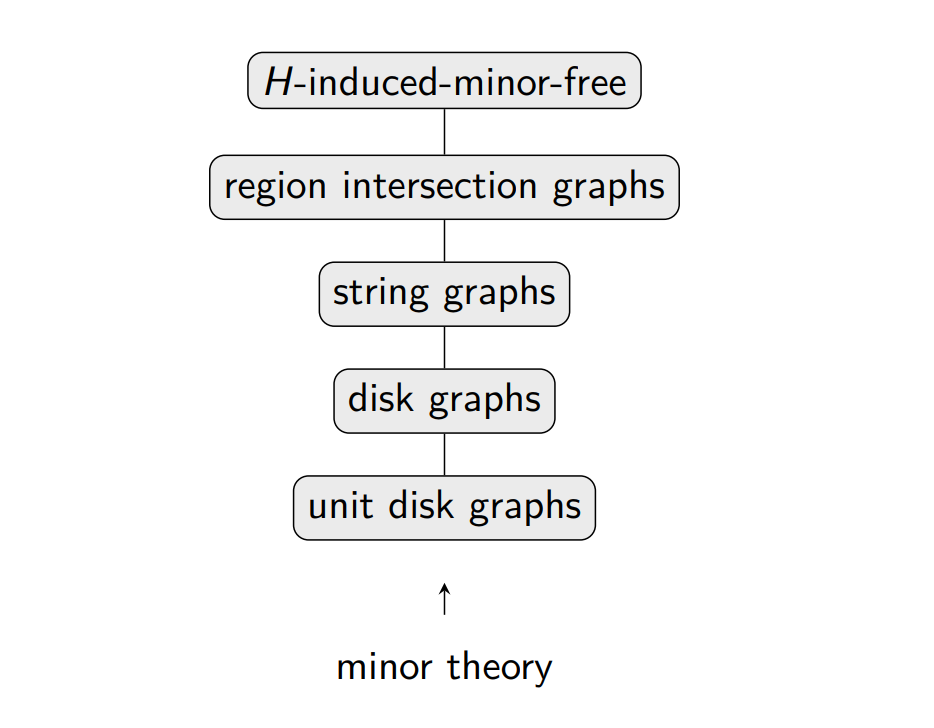

Édouard surveyed recent developments in geometric intersection graphs from the minor and induced minor theory perspective.

The talk covered:

- Balanced separators and clique-based separators.

- Robust vertex contraction decomposition, a new technique for designing EPTASes for geometric intersection graphs.

- Bounded weak-diameter colorings.

- String graphs.

2.3. Dynamic Algorithms in Geometry

Wolfgang surveyed serveral dynamic geometric problems:

- Dynamic planar lower envelopes of lines, a classical problem in geometry.

- Dynamic planar lower envelopes of pseudolines.

- Dynamic lower envelopes in \(\mathbb{R}^3\).

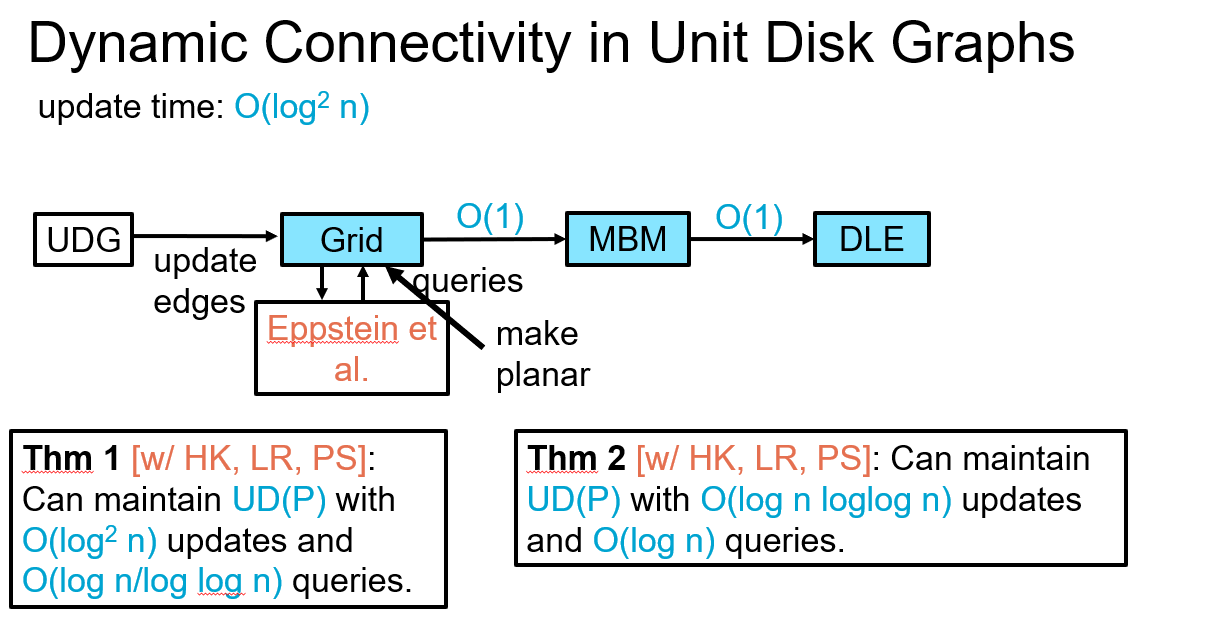

- Dynamic connectivity of unit-disk graphs. Here, vertices (unit disks) are dynamically inserted/deleted, and the edges are defined implicitly by the intersections of the disks. Therefore, one vertex insertion/deletion could induce \(\Omega(n)\) edge insertions/deletions. This is the major challenge.

2.4. Plane Constant Spanners

Jit surveyed the constructions and online routing schemes for plane spanners with \(O(1)\) stretch. A plane spanner is a spanner for point sets in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with an added constraint that the straight line drawing of the edges in the spanners must be a planar graph.

In an online routing scheme, one wants to send a message from a source vertex to a target vertex. Upon receiving a message, a vertex must decide to forward the message to one of its neighbors. The basic information for the decision contains (a) the current vertex, (b) the source vertex, and (c) the list of neighbors of the current vertex. Depending on the model, the algorithm might have some local memory and some additional bits of information stored at the current vertex.

The talk covered:

- Delaunay triangulation, which is a basic plane spanner of \(O(1)\) stretch, and a routing scheme on the triangulation.

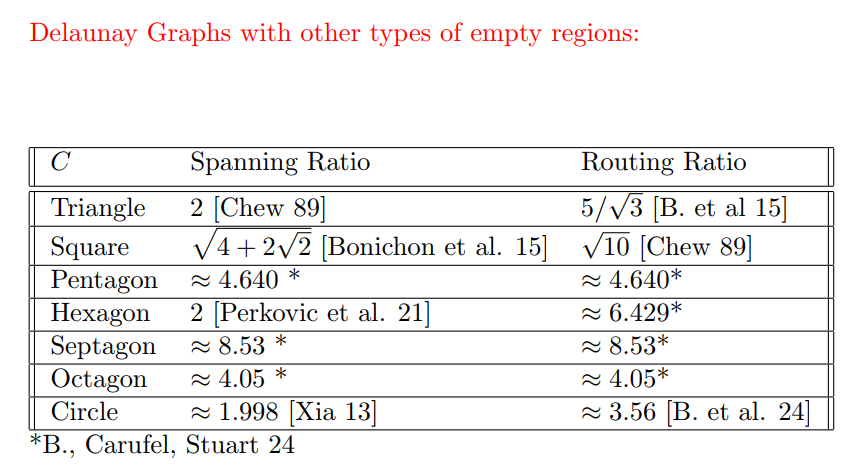

- Delaunay graphs with other types of empty regions. The standard Delaunay triangulation uses circles as empty regions. When one replaces circles with triangles, squares, pentagons, etc., one gets different types of Delaunay graphs. See the figure below for state-of-the-art results.

- Bounded degree spanners.

2.5. Young Researcher Presentations

We had four presentations by four junior participants, each giving an overview of their research. In alphabetical order, they are:

- Jonathan Conroy currently is a 3rd PhD student at Dartmouth College. I have been working with Jonathan on a few projects, and some of his works were previously covered in this blog.

- Lazar Milenković is defending his PhD thesis. I wrote a few papers with Lazar on Euclidean spanners, and low-diameter spanners. Among other things, Lazar has an impressive strength in manipuliating mind-blowing functions.

- Sampson Wong is currently a postdoc at the University of Copenhagen under a Marie Curie fellowship. Sampson works on a wealth of topics in computational geometry: Fréchet distance, spanners, and geometric graphs.

- David Zheng recently completed his PhD at UIUC. David works on graphs and geometry. An amazing recent result of David is an elegant construction of weighted distance oracles (and other results) for minor-free graphs using VC dimension. Despite building on my own work, David’s paper taught me how to think about VC dimension in a cleaner way.

3. On Preparing a Dagstuhl Proposal

The application for a workshop is very simple, including:

- A 4-page proposal.

- A short CV of each organizer.

- A list of about 40 people to be invited as participants (for a small seminar like ours).

One of us, Csaba Tóth, has experience organizing Dagstuhl seminars in the past, so navigating the process became much easier. If you are thinking about organizing one, it is very helpful to have someone with experience in the organizing team.

We submitted our application around mid-April 2024, and the decision was given on July 12, so the review was about 3 months.

Once the proposal was accepted, Dagstuhl invited all the participants in the list that we provided. We also provided another list of about 20 people to invite in the 2nd round.

All in all, I had a very good experience with the process. Given the relatively small amount of work per organizer, I would want to organize another seminar again in the future. If you are thinking about organizing one, go for it! And if you want to hear more about my personal experience, shoot me an email.

4. Random Stuffs

Many of us got to Frankfurt and then to Dagstuhl. It is not so easy to get to Dagstuhl; some coordination between participants would make the travel easier. I took a train from Frankfurt to Türkismühler and then a taxi from Türkismühler to Dagstuhl.

Many people left on Friday, and some stayed until Saturday. I left on Friday for Frankfurt to see an English play with Karthik at the English Theatre Frankfurt. However, the theatre has two different locations, and we went to the wrong one. Once we figured out the right location, it was already too late, and we had to abandon the plan. It’s a shame!