In a recent preprint with amazing collaborators that I met during a workshop on geometric spanners at the Rényi Institute, we looked into spanners for planar domains such as polygonal domains or polyhedral terrains. One problem arising from this work is constructing a non-Steiner tree cover for tree metrics. So what is it?

Given an edge-weighted tree \(T\) and a subset of terminals \(K\subseteq V(T)\), a non-Steiner tree cover with stretch \(\alpha \geq 1\) is a collection of trees \(\mathcal{T}\) such that:

- [Non-Steiner] every tree \(X\in \mathcal{T}\), \(X\) only contains vertices of \(K\), i.e., \(V(X) = K\).

- [Dominating] for every tree \(X\in \mathcal{T}\), and for every two terminals \(t_1,t_2\in K\), \(\delta_T(t_1,t_2)\leq \delta_X(t_1,t_2)\).

- [Stretch] for every two terminals \(t_1,t_2\in K\), there exists a tree \(X\in\mathcal{T}\) such that \(\delta_X(t_1,t_2)\leq \alpha\cdot \delta_T(t_1,t_2)\).

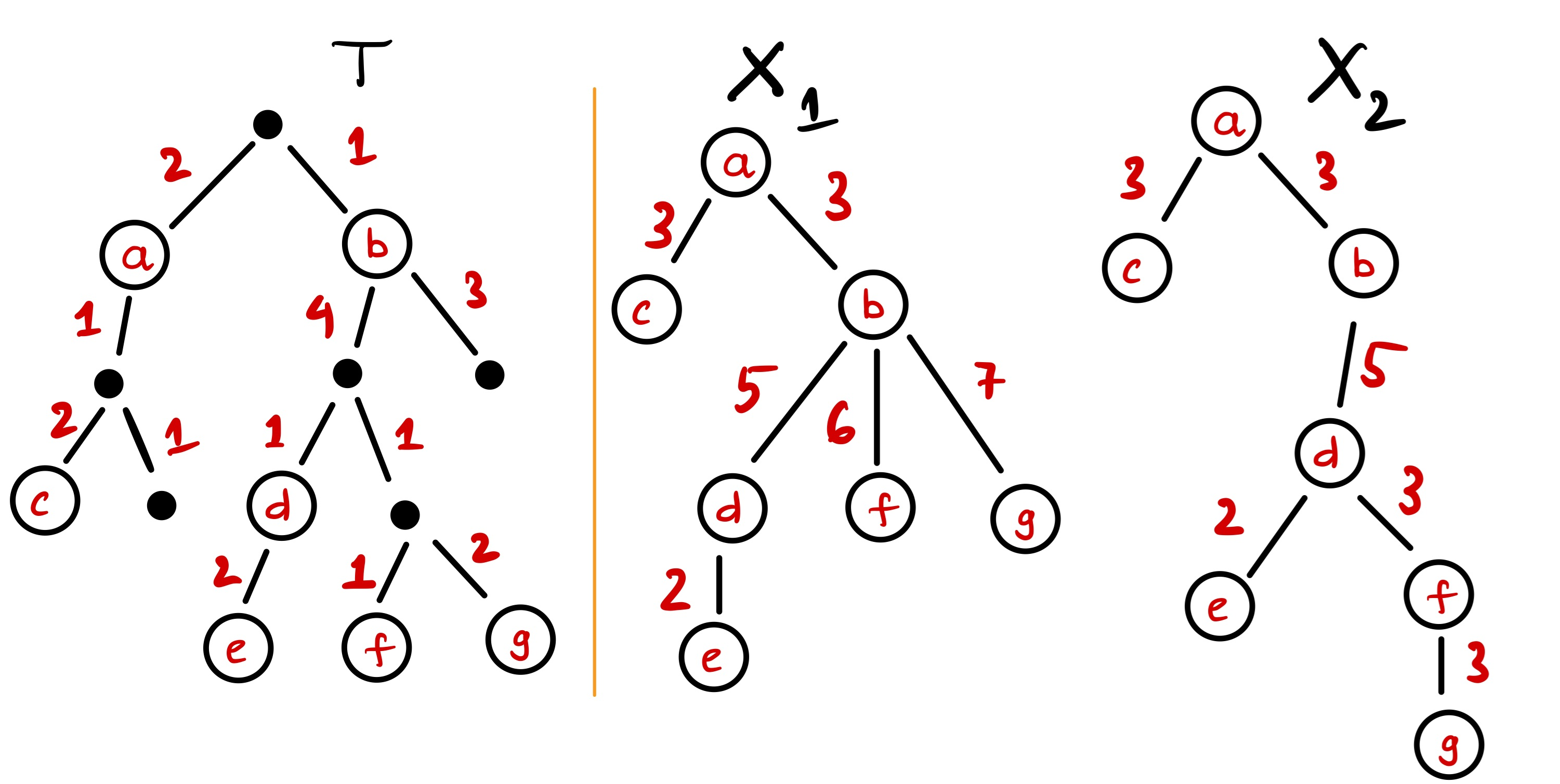

Figure 1: A Steiner-free tree cover with 2 trees for \(T\) on the left. The distortion is \(\alpha = 4/3\) realized by the vertex pair \({e,g}\).

Figure 1: A Steiner-free tree cover with 2 trees for \(T\) on the left. The distortion is \(\alpha = 4/3\) realized by the vertex pair \({e,g}\).

The goal is to construct a non-Steiner tree cover with a small size (number of trees) and small stretch \(\alpha\) for any given tree \(T\) and the terminal set \(K\).

The tree \(T\) can be seen as a Steiner tree for the terminal set \(K\): we often refer to vertices in \(T\setminus K\) as Steiner points. In some applications, we want to remove the Steiner points while preserving (approximately) the tree structure and the distances between terminals. One way to achieve this goal is a non-Steiner tree cover: no Steiner vertices, having a few trees (approximately preserving the tree structure), and low stretch (approximately preserving distances).

The discussion above may remind you of the Steiner point removal problem introduced by Gupta: given an edge-weighted tree \(T\), a subset of terminals \(K\subseteq V(T)\), construct another tree \(X\) that only contains \(K\) and \(\delta_T(t_1,t_2)\leq \delta_X(t_1,t_2) \leq \alpha\cdot \delta_X(t_1,t_2)\) for every two terminals \(t_1,t_2\). The goal is to minimize \(\alpha\). The solution to the Steiner point removal problem can be seen as a non-Steiner tree cover with a single tree. Here, we allow more than one tree and hope to achieve a smaller stretch \(\alpha\). More generally, we are interested in understanding the trade-off between two parameters: stretch and the number of trees.

For a single tree case (Steiner point removal problem), Gupta achieved stretch \(\alpha = 8\), and a matching lower bound of \(8-o(1)\) was shown later by Chan, Xia, Konjevod, and Richa. There is a much easier lower bound for \(\alpha \geq 2\): the star graph. Specifically, \(T\) is a star with terminals being the leaves, and every edge has weight 1. For this case, the best solution with stretch \(2\) is to construct a star rooted at a terminal with leaves being other terminals.

The star graph also points to a simple lower bound for non-Steiner tree cover: for \(\alpha < 2\), the number of trees must be \(n - 1 = \Omega(n)\) where \(n\) is the number of terminals. But for the star graph, a single tree achieves \(\alpha = 2\). Can we achieve stretch \(\alpha = 2\) with a constant number of trees? If not, with a constant number of trees, could we break the stretch \(8\) known for a single tree? In trying to understand these questions, we stumbled upon a surprising answer: for stretch \(2\), \(\Omega(\log n)\) trees are both necessary and sufficient. Furthermore, with a constant number of trees (depending on \(\epsilon\)), one can achieve stretch \(2+\epsilon\) for any constant \(\epsilon \in (0,1)\). This provides a sharp transition around stretch \(2\).

Theorem: Let \(\alpha\geq 1\) be the stretch parameter, and \(\epsilon\in (0,1)\) be any given constant. Let \(T\) be an edge-weighted tree and \(K\subseteq V(T)\) be any set of \(n\) terminals:

- If \(\alpha = 2+\epsilon\), then \(O(1)\) trees suffice: we can construct a non-Steiner tree cover for \(K\) of size \(O(1)\) and stretch \(2+\epsilon\). The number of trees is \(O(\epsilon^{-2}\log(\epsilon^{-1}))\).

- If \(\alpha = 2\), then \(O(\log n)\) trees suffice. Furthermore, \(\Omega(\log n)\) trees are necessary: there exist a tree and a terminal set such that any tree cover with stretch \(2\) for the terminals must have \(\Omega(\log n)\) trees.

- If \(\alpha = 2 - \epsilon\), then \(\Theta(n)\) trees are both necessary and sufficient.

A few words about technical ideas: Item 3 is relatively straightforward: the lower bound was discussed above, and the upper bound is by taking a single-source shortest path (SSSP) tree rooted at each terminal. (By single-source shortest path tree rooted at a terminal \(t\), I mean the star obtained by connecting every other terminal \(t’\) to \(t\) via a direct edge with weight \(d_T(t,t’)\).)

For stretch \(2\), the upper bound is obtained by recursively taking the terminal \(t\) closest to the centroid vertex of \(T\) and making an SSSP tree rooted at \(t\). The recursion depth is \(O(\log n)\), giving \(O(\log n)\) trees. Proving the lower bound, that one needs \(\Omega(\log n)\), is more complex. Indeed, we proved a stronger lower bound. We show that there exists a tree \(T\) and \(n\) terminals such that any graph with stretch \(2\) that contains only the terminals must have \(\Omega(n \log n)\) edges. As the union of a non-Steiner tree cover with \(k\) trees is a graph with \(O(n\cdot k)\) edges, we get \(k = \Omega(\log n)\). The lower bound instance \(T\) is a comb graph (with appropriate edge weights), and the terminals are the leaves of \(T\).

For stretch \(2+\epsilon\), the construction of the tree cover is rather complicated. The basic idea is to root the tree \(T\), chop it into multiple layers, and appropriately group these layers. In the paper, we show how one can achieve stretch \(3+\epsilon\) with just chopping and grouping, and then we show how to improve the stretch to \(2+\epsilon\) with more aggressive grouping. If you find this vague but intriguing, check out the paper.